- HOME

- OPINION

- ON GROUND

- INTERVIEW

- INDIA

- NewsGram USA

- WORLD

- न्यूजग्राम

- POLITICS

- ENTERTAINMENT

- CULTURE

- LIFESTYLE

- ECONOMY

- SPORTS

- Jobs / Internships

- Misc.

- NewsGram Exclusive

Following the mandatory E20 rollout in India earlier this year, the public and opposition have raised several criticisms against the policy.

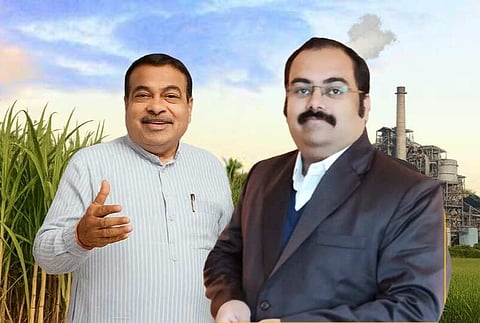

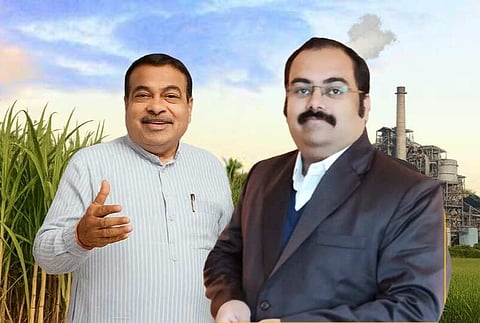

Critics have accused Nitin Gadkari of favouring his son's ethanol production business.

Doubts have arisen around misrepresentation and misregulation of the company.

The Central Government began its push to make E20 — petrol blended with 20% ethanol — the national norm in April 2023. By April 2025, the initiative had been rolled out nationally and E20 was made mandatory. The government says the move cuts import bills, supports sugarcane farmers, and lowers emissions. But the speed of the rollout and the ripple effect on the market have raised uncomfortable questions about disclosures, regulatory attention, and possible conflicts of interest.

The general public and opposition parties have hit out against two aspects of the policy: the mandatory rollout, which critics claim violates consumers’ right to choice, and the unfair advantages gained by some companies in the ethanol chain, like those tied to Union Minister of Road Transport and Highways, Nitin Gadkari.

Gadkari has been a vocal promoter of E20 since long before the mandatory rollout. Cian Agro Industries & Infrastructure Ltd is promoted and managed by his son Nikhil Gadkari, while another entity in the sector, Manas Agro, is linked to his other son Sarang Gadkari.

Opposition parties, led by the Congress, have pressed conflict-of-interest claims. They argue that Gadkari’s policy support and public push for ethanol blending align suspiciously with the surge in value of his sons’ ethanol businesses. The Congress points to Cian’s jump from about ₹18 crore in revenue in June 2024 to ₹523 crore in June 2025, and its stock rising nearly 2,184% within months. Rahul Gandhi and party leaders have called for independent probes. In Q1 FY24, Cian made a profit of around ₹10 lakh. By Q1 FY26, these soared to ₹52 crore — a nearly 30 times jump in sales.

Gadkari has strongly denied involvement. He stated that Cian was founded before the blending policy and claimed that the company’s ethanol output makes up less than 0.5% of India’s total ethanol production. He also said he had no role in awarding tenders or setting pricing and described the allegations as part of a “paid campaign” by import interests.

Cian began by selling edible oils and spices before diversifying its operations. According to Cian’s disclosers, the majority of its gains came from its subsidiaries. Cian reports results not just from ethanol but from sugar, distilleries, power, infrastructure, healthcare and more.

A large portion of gains is classified under “other income” — items like lease reductions or fair value gains — which help lift net profit significantly. Finshots, an independent market reporting agency, has pointed out that Cian’s filings do not clearly break down ethanol capacity or revenue contributions by each subsidiary.

It further pointed out mismatches in the company’s cash flow statements and balance sheets, which auditors have signed off on. Finally, it drew attention to worrying trends in the company’s shareholdings. There has been an overall decline in stakes of promoters, with a majority of the holdings being pledged. Institutional holdings also account for less than 0.2% of the total, meaning any risk falls squarely on retail investors.

The company’s market cap has risen from ₹100 crore last year to about ₹2,000 crore today. Given this explosion, the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) has placed Cian under ASM (Additional Surveillance Measure) Stage 4 – which implies maximum surveillance – to curb abnormal price swings. The stock has already delivered returns multiple times its original share price.

But despite these trends, which would normally warrant further scrutiny and detailed investigations, no such initiative has been taken by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI).

These signals point to potential misrepresentation and misregulation. The combination of rapid expansion, heavy reliance on other income, minimal disclosures, and promoter pledging raises some questions: is the Gadkari ethanol business being overvalued? If it is, who will bear the consequences of the fallout? If not, why is the company not facing the same regulatory scrutiny as other ethanol producers? [Rh/Ds]