- Home

- न्यूजग्राम

- NewsGram USA

- India

- World

- Politics

- Entertainment

- Culture

- Lifestyle

- Economy

- Sports

- Sp. Coverage

- Misc.

- NewsGram Exclusive

- Jobs / Internships

Inside the walls of Tehran’s Evin Prison — a space synonymous with repression and pain — Vida Rabbani created a language of resistance through painting. Using bedsheets as canvas, smuggled brushes, and colors brought in tube by tube, she documented the intimate textures of carceral life in Iran’s most notorious women’s prison ward. Her work, both courageous and tender, transformed confinement into a form of creation. From portraits of fellow political prisoners to layered renderings of institutional staircases, Rabbani’s paintings gave a visual voice to the unseen lives of women navigating both isolation and solidarity behind bars. Her images were not just acts of self-expression; they became acts of collective preservation.

Rabbani, a journalist and former reporter at Shargh Daily and Seda Weekly, had never considered herself a professional artist. But following her 2022 arrest during Iran’s anti-government protests and her subsequent sentencing to more than 11 years combined over two cases, she began to paint in earnest. She spent 32 months in prison before her sentence was suspended, and she was released from Evin Prison. The Iranian authorities may have tried to stifle her speech, but through brushwork and imagery, she documented what she could not publish: the contours of captivity and the quiet, defiant rituals of daily survival.

“In prison, limitations sharpen the imagination,” she said. “When space and materials are scarce, your mind does the work of finding freedom.” Rabbani’s art evolved in secret, sometimes illuminated only by a desk lamp late at night, and often under the threat of confiscation. Aided by fellow inmates, she covertly assembled acrylics and brushes, stretching fabric over wooden frames salvaged from the prison’s carpentry shop.

See Also: Article 370 Abrogation: Kashmir growth story going steady for 6 years

While her early murals — such as one of the endangered Persian cheetah Pirouz — were painted directly onto courtyard walls, Rabbani soon turned inward, sketching rooms, beds, and portraits that conveyed not just presence but memory. The paintings, all modest in scale yet expansive in emotional reach, trace a remarkable arc of visual storytelling under constraint.

In an interview with Global Voices, Vida Rabbani spoke about documenting the visual culture of prison, the improvisational methods behind her work, the emotional toll and healing of art-making under surveillance, and how painting became her most powerful form of witness.

Omid Memarian (OM): When did you first start painting, and how did it evolve alongside your work in journalism?

Vida Rabbani (VR): Memories start differently for everyone. I don’t remember exactly how old I was, but ever since I can recall, I have been drawn to painting and crafting. We were a middle-class family living in a remote town in southern Iran. I was obsessed with stationery shops — still am. I remember only owning two dolls throughout my childhood, but I was in love with picture books, coloring supplies, and playdough. My mother was protective of my tools, making sure I didn’t ruin them.

Around the age of four, I began painting. I vividly remember the joy of finally receiving a six-color gouache set and a box of markers. In school, I was considered one of the better painters, even placing third in a national competition once. But instead of encouragement, my family saw my interest in art as a threat, especially my mother, who dreamed I’d become a doctor. She feared painting would distract me from studying. In third grade, I secretly enrolled in an art class and continued for a few years. But I didn’t return to painting seriously until I was imprisoned in Evin.

OM: What themes did you explore in your prison paintings, and what did they mean to you?

VR: It began when I helped a fellow inmate with a drawing, and others responded so warmly that I picked up my own brush. The enthusiasm of others encouraged me to request painting supplies, which my husband brought to the prison.

I started by painting murals. One depicted Pirouz sprinting across a wall, dedicated to fellow inmates and environmental activists Sepideh Kashani and Niloufar Bayani. Another mural revealed a forest path behind crumbling bricks, symbolizing escape. Authorities painted over them, claiming they were politically subversive, and banned any more art supplies.

Near the 2024 New Year, I spent 10 to 12 days painting prison walls to refresh the space. What began as a way to brighten our environment became a daily act of resistance and renewal.

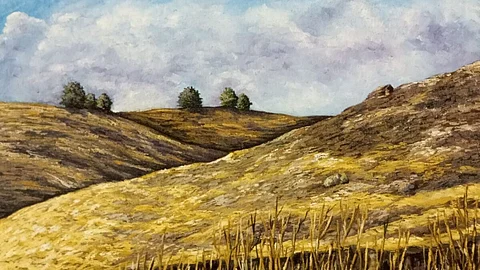

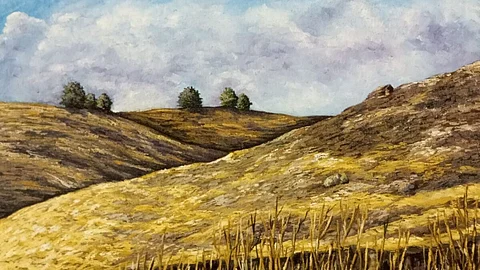

Later, other inmates asked me to paint their beds, rooms, or corners of the ward to share with their families. This inspired me to document the women’s ward in a way others outside could see. My first interior painting was a view of the Evin hills from my cell window.

Although I had never painted portraits before, I wanted to show what imprisonment did to people’s faces and spirits. I painted Golrokh Iraee — my first-ever portrait. Later, when Pakhshan Azizi received a death sentence, my friend Hasti Amiri, who was about to be released, asked me to paint Pakhshan so she could raise awareness. I painted it by lamplight in bed the night before her release. Since photography was banned, drawing became the only way to visually archive people and spaces in prison.

OM: Given the restrictions, how did you get art supplies in prison?

VR: One of the prisoners helped by smuggling in oil paints and brushes during family visits, hiding them in her clothes. It took months to gather enough supplies.

Eventually, for the New Year, Narges Mohammadi [the 2003 Nobel Peace Laureate] convinced the authorities to let us bring in a larger shipment of materials. I took advantage of this to sneak in proper acrylic paints among the wall paints.

OM: What obstacles did you face while painting in prison, and how did you overcome them?

VR: There were many. I had no canvases, so I repurposed a wooden frame from the prison’s carpentry workshop and stretched bedsheets over it with nails. That’s why all my paintings are 70 x 50 cm [19.6 x 27.5 inches]. Paints were limited — white, especially, ran out quickly — so I used color sparingly. The paint layers are very thin as a result.

When my brushes wore out, I sat in front of the warden’s office all day until they agreed to give me a palette knife and two brushes, on the condition that I wouldn’t take any artworks out without permission.

OM: What impact did painting have on your mental and emotional state during imprisonment?

VR: Though I never felt useless in prison, painting gave me new energy and purpose. I’d wake up excited to continue my work. I observed the ward constantly, looking for new subjects. I knew I wouldn’t have time to paint everything I wanted before my release, so I sketched prolifically to continue later outside. It made time pass faster and transformed my prison experience into an artistic opportunity I didn’t want to lose.

OM: How did other inmates and prison staff respond to your work?

VR: It was the inmates’ reactions that encouraged me most. I had initially planned to focus on reading and studying, but their enthusiasm pulled me into art. During the New Year, when I painted the stairwell, they constantly checked in on me, brought me food and coffee, and made me feel like I was doing something meaningful.

See Also: Trump Arranges Zelenskyy Putin Meeting After White House Talks

Some nights, I’d come back exhausted and find a meal waiting on my bed. I don’t think I’ve ever felt as appreciated or purposeful as I did during those days. One inmate told me the murals had brought the spirit of Nowruz into the ward.

OM: Did the experience influence your artistic style or technique?

VR: I wasn’t a trained artist with a defined style. I had a basic understanding of various techniques but no formal education. I never liked photorealism — too much detail doesn’t appeal to me. I prefer visible brushstrokes and texture. I avoided blending colors too smoothly.

Still, when I look at my prison paintings together, I see clear growth. My technique improved dramatically, and I gained much more confidence.

OM: Now that you’re free, do you plan to exhibit or publish your prison paintings?

VR: Yes, absolutely. I painted for two reasons: to make the prison more livable, and to show others what it looked and felt like inside. If I can exhibit these works, I would be thrilled. They were never just for me; they were always meant to be shared.

OM: Do your paintings carry a specific message?

VR: I tried to capture the atmosphere of prison — sometimes joyful, sometimes bleak. I wanted to reflect the rhythm of life inside. Emotions are heightened in prison. Grief, joy, solitude, solidarity; they're all more intense than on the outside. I hope that comes through in my work.

OM: Have other imprisoned artists inspired you?

VR: During a short leave from prison, I saw a BBC piece about a British man who began painting during his 13-year sentence for heroin trafficking. He said art changed his life, and after his release, he became a professional painter and even won awards. I joked with my friends that my sentence was too short; if I’d had 10 more years, maybe I’d have become a prize-winning artist too.

OM: Artists like Richard Dadd created remarkable works while imprisoned. Do you feel that incarceration stimulated your creativity in any way?

VR: I don’t think it’s just a cliché that limitations fuel creativity. When your physical environment and resources are restricted, you’re forced to rely more on your imagination to find solutions and adapt. That mental effort pushes the mind into motion. Perhaps psychologists could explain it better, but for me, that’s precisely what happened.

(GlobalVoices/NS)

Also Read: