- Home

- NewsGram USA

- India

- न्यूजग्राम

- World

- Politics

- Entertainment

- Culture

- Lifestyle

- Economy

- Sports

- Sp. Coverage

- Misc.

- NewsGram Exclusive

- Jobs / Internships

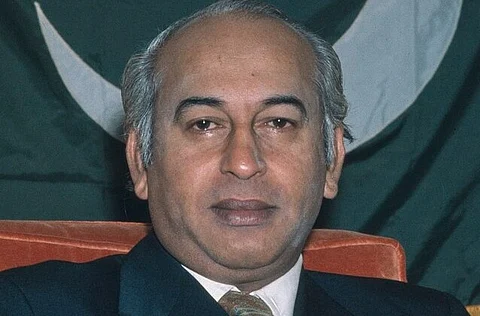

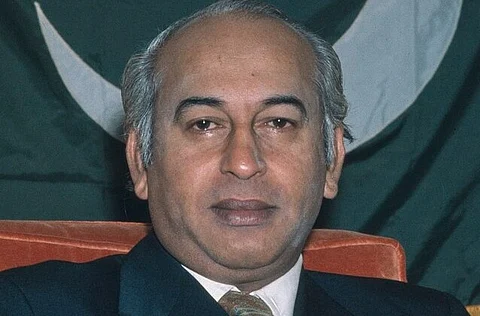

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, former Prime Minister of Pakistan and founder of the Pakistan People’s Party, was executed in 1979

After his execution, prison authorities photographed Bhutto’s genitals allegedly to check if he was circumcised

The act was revealed in Colonel Rafiuddin’s book Bhutto ke Akhri 323 Din

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, one of Pakistan’s most influential and controversial political leaders, met not only a tragic end but also a disturbingly humiliating one. After being executed on April 4, 1979, under General Zia-ul-Haq’s military regime, a deeply unsettling act followed—Bhutto’s body was photographed, not for standard identification, but to capture his genitals. This action, as later revealed, was allegedly intended to determine whether Bhutto had undergone circumcision—a religious rite marking male Muslim identity.

Bhutto, the founder of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), served as Pakistan’s fourth President and ninth Prime Minister. Known for his charisma and populist policies, he was the architect of Pakistan’s 1973 Constitution and introduced landmark reforms such as land redistribution, labour rights, and nationalization of industries. Yet, his rise also came with authoritarian tendencies and political crackdowns, which earned him both staunch followers and powerful enemies.

In 1977, his government was overthrown in a military coup led by General Zia. A controversial trial followed, accusing Bhutto of authorizing the murder of a political opponent. Despite international outcry over the fairness of the proceedings, Bhutto was sentenced to death and hanged in Rawalpindi Central Jail.

But the state's vengeance did not stop with his execution. According to Colonel Rafiuddin, who served as Bhutto’s security officer in prison and documented his final months in the book Bhutto ke Akhri 323 Din ("The Last 323 Days of Bhutto"), a post-mortem photograph was deliberately taken to examine whether Bhutto had undergone khatna (circumcision). In Pakistan, a Muslim-majority nation where circumcision is near-universal and seen as a fundamental part of male Muslim identity, this act appeared less about religion and more about humiliating Bhutto—undermining his Islamic credentials even in death.

Colonel Rafiuddin’s account does not delve deeply into Bhutto’s emotional or political reflections but includes startling moments. In one instance, Bhutto is quoted as saying, “Rafi Sahib, although I am a great sinner, perhaps declaring the Ahmadis as non-Muslims by law might compensate for my sins, and Allah might forgive me because of this good deed.” This chilling reflection underscores the moral and political weight Bhutto carried in his final days.

The decision to question his religious identity posthumously, especially in such a degrading way, highlights the extent to which the Zia regime sought to erase Bhutto’s legacy. In Islamic tradition, even the dead are granted dignity. The concept of ḥurmat al-jasad (sacredness of the body) in Islamic jurisprudence upholds the bodily sanctity of individuals, forbidding impolite or disrespect after death. That Bhutto’s body was used to cast criticism on his faith is a stark violation of these principles.

This episode is not just about Bhutto—it is a grim symbol of how authoritarian regimes weaponize religion, morality, and even corpses to crush dissent and control narratives. Despite these attempts to tarnish him, Bhutto remains one of Pakistan’s most studied and debated figures. His legacy, both admired and critiqued, continues to shape the country’s political discourse. But the disturbing events surrounding his death reveal more about the insecurities of the regime that killed him than about the man himself. [Rh/VP]