- Home

- न्यूजग्राम

- NewsGram USA

- India

- World

- Politics

- Entertainment

- Culture

- Lifestyle

- Economy

- Sports

- Sp. Coverage

- Misc.

- NewsGram Exclusive

- Jobs / Internships

A 10-hour discussion was held in the Winter Session of Parliament to mark the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram

While the government highlighted the song’s unifying legacy, Opposition leaders accused it of politicizing history

Written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in the 1870s, Vande Mataram remains culturally significant but historically debated

It has been 150 years since our national song Vande Mataram was written, marking an important moment in Indian history. The song shaped patriotism and inspired countless freedom fighters who contributed to India’s freedom struggle. Over the decades, it has also sparked debate because of its religious imagery and political interpretations. As India marks the 150th anniversary of this iconic hymn, it has once again become a point of political debate in Parliament and has resurfaced in the political arena.

Adopted by the Constituent Assembly in 1950, Vande Mataram is routinely sung at official events, including parliamentary proceedings, schools, and government functions. In 2017, the Madras High Court even mandated its recitation in educational and government institutions in Tamil Nadu.

During the Winter Session of Parliament on December 8, 2025, a discussion on Vande Mataram was initiated to mark its 150th anniversary. Prime Minister Narendra Modi opened the 10-hour debate. Many leaders participated in the debate—some praised the song’s historic legacy, while others criticized the government for focusing on a historical hymn instead of the pressing issues facing the country.

The debate opened with PM Narendra Modi, who praised the song, its legacy, and its role in inspiring generations during the freedom struggle. “Vande Mataram is a mantra, a slogan which gave energy, inspiration, and showed the path for sacrifice and penance to the freedom movement,” the Prime Minister said. He stated that the song united people across India to fight colonialism, adding that different ideologies were united by the single slogan ‘Vande Mataram’.

PM Modi then turned his criticism toward the Congress and the Jawaharlal Nehru government, claiming that Vande Mataram was “betrayed” by them. He cited a letter written by Nehru to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, which allegedly stated that the song could irritate Muslims. Modi further accused the Congress of compromising the sacred song before the Muslim League and argued that the song was “partitioned first.” He claimed that the Congress’s removal of certain stanzas in 1937 “sowed the seeds of division” in India. The BJP framed the debate as an issue of civilizational pride and national identity.

After the BJP’s speeches, several Opposition leaders responded. TMC MP Mahua Moitra accused the BJP of politicizing Vande Mataram ahead of the 2026 Bengal elections, calling the party’s focus “a badly scripted comedy.” She criticized the ruling party for ignoring urgent issues such as water shortages, pollution, agricultural distress, and administrative failures. She argued that debating history while neglecting present-day challenges was misguided.

DMK MP A. Raja referred to historical evidence to argue that communal tensions surrounding Vande Mataram were amplified by certain nationalist leaders rather than the song itself. He questioned the Prime Minister, asking who was responsible for dividing both the country and Vande Mataram. Raja added that there are reasons to believe that the song was not only against the British but also perceived as being against Muslims.

The Congress, meanwhile, reiterated that the 1937 Congress Working Committee (CWC) decision to limit public singing to the first two stanzas was based on inclusivity and Rabindranath Tagore’s guidance. Priyanka Gandhi stated, “The so-called objection against the remaining stanzas of Vande Mataram was manufactured by the communalists.” She emphasized the rich history of the song and the many leaders associated with it.

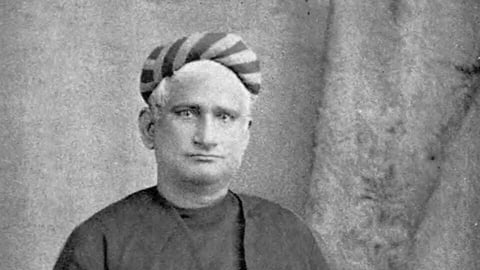

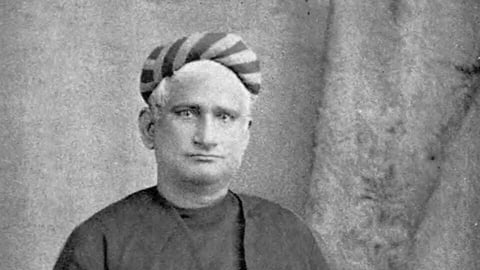

Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, one of the most influential thinkers and writers of 19th-century India, composed the original poem in the 1870s. It was first published in the literary journal Bangadarshan on November 7, 1875. The first two stanzas—written largely in Sanskrit with some Bengali—depicted the motherland as a benevolent figure. Vande Mataram translates to “Mother, I Bow to Thee.”

The poem was initially a private expression of devotion and remained unpublished for several years. In 1882, Chatterjee included it in his novel Anandamath, serializing additional stanzas that invoked Hindu goddesses such as Durga, Lakshmi (Kamala), and Saraswati. The song was first sung publicly by Rabindranath Tagore at the 1896 annual convention of the Indian National Congress in Calcutta, after which it gained immense popularity.

By the early 20th century, Vande Mataram became a rallying cry during the Swadeshi movement of 1905, following Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal. However, the song’s explicit references to Hindu deities created discomfort among some Muslim communities, leading to longstanding debates over inclusivity within the nationalist movement.

By the 1930s, the Congress faced criticism from Muslim leaders who found the later stanzas exclusionary. Muslims in Bengal, in particular, objected to the song’s religious symbolism. During debates in 1937, Subhas Chandra Bose wrote to Tagore for guidance on whether the full song or selected portions should be sung at public events.

Tagore replied that the first two stanzas were entirely non-sectarian and could be sung by all Indians, but the later stanzas—which portrayed the motherland as the goddess Durga—introduced religious elements unsuitable for universal acceptance. Based on this advice, the CWC resolved that only the first two stanzas would be sung at national gatherings. Individuals were free to sing other songs if they preferred. This decision drew criticism from Hindu nationalists.

The debates surrounding Vande Mataram have deep roots. Early 20th-century Muslim skepticism grew due to the Bharat Mata motif and the song’s associations with Hindu symbolism. By the late 1930s, Muslim leaders openly opposed the song and launched campaigns against its public use. At a meeting in Lucknow, leaders argued that references to Hindu deities were idolatrous and hurt Muslim sentiments.

Despite the controversy, Vande Mataram played a powerful and unifying role in India’s freedom struggle. It became a nationalist anthem, inspiring mass movements, rallies, and patriotic fervor. Acknowledging its historic and cultural significance, on 24 January 1950, Dr. Rajendra Prasad declared Jana Gana Mana as the national anthem and Vande Mataram as the national song, giving both equal honor and status. Even today, Vande Mataram continues to shape India’s cultural, political, and historical landscape.

[Rh]

Suggested Reading: