- Home

- NewsGram USA

- India

- न्यूजग्राम

- World

- Politics

- Opinion

- Entertainment

- On Ground

- Culture

- Lifestyle

- Economy

- Sports

- Sp. Coverage

- Misc.

- NewsGram Exclusive

- Jobs / Internships

- Interview

Islam began in the early 7th century in Mecca with Prophet Muhammad, who, according to Islamic tradition, received divine revelations

After initial resistance in Mecca, Muhammad’s migration to Medina marked a turning point where religious leadership merged with political authority

Under the early caliphs, Islamic rule spread swiftly across Arabia, the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Europe, transforming Islam into a major religion

Islam emerged in the early 7th century in the Arabian Peninsula. There are different approaches to history and many conspiracy theories about incidents that happened. But what is the traditional account? How did Islam start? Who was Muhammad? There have been many questions and attacks on Islam recently; many question whether Islam is real or whether Muhammad existed or not. The story of the existence of Islam can be a building block to understanding the religion as a whole. So let’s see how Islam as a religion began and came into being.

Let’s see what Raymond Ibrahim explains about the history of Islam, its beginnings, and how it is connected to other religions. Ibrahim is an author and translator from America who has studied Arabic history and Islam. He has written many books, particularly on Islam and the interaction of Islam with Christianity. So, let’s see how it all begins.

According to the traditional Islamic account, the religion began with Muhammad. Muhammad was born around 570 AD in Mecca, in the Arabian Peninsula. Orphaned at a young age and raised by relatives, Muhammad lived an ordinary life; Ibrahim said he was a camel driver. He belonged to the Quraysh tribe in Mecca, which was considered noble, but he himself was of lesser nobility, living a relatively ordinary life.

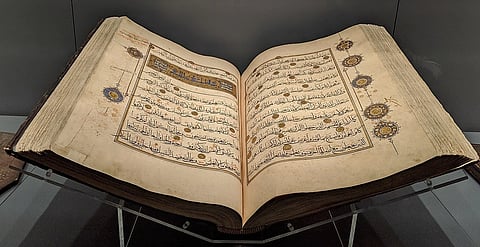

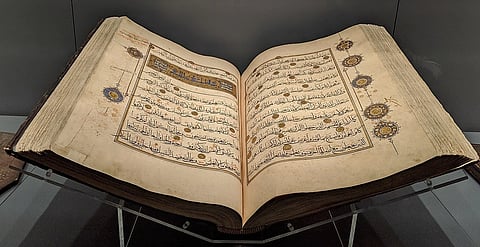

Around the age of 40, around 610 AD, Prophet Muhammad claimed to receive revelations when he began retreating to a cave outside Mecca for meditation. It was there, Muslims believe, that he received his first revelation from the angel Gabriel. These revelations, which continued over more than two decades, were later compiled into the Qur’an, Islam’s holy book. Raymond Ibrahim explains that the Arabic word Qur’an itself means “recitation.” Muhammad’s early teachings are known as the Meccan verses of the Qur’an.

Muhammad preached belief in one God and placed himself in a line of earlier prophets such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, whom Islam regards as a prophet, not the son of God. As Ibrahim notes, Muhammad positioned himself as the final prophet, saying he came to correct what he saw as distortions introduced by Jews and Christians into earlier revelations. This claim placed Islam both within and in tension with existing religious traditions. Ibrahim explained with an example: “When it comes to the person of Jesus, he was just a prophet, but the Christians made him into the son of God.”

In his early years in Mecca, Muhammad had very few followers and faced resistance and ridicule from local tribes. During this period, the tone of his message was largely peaceful. Verses from this time (610–622 AD) emphasised tolerance and coexistence. As Raymond Ibrahim explains, when Muhammad was weak and outnumbered, the message was “you have your religion and I have mine.” So there are moderate verses in the Qur’an which moderate Muslims follow, such as Surah Al-Baqarah (2:256), which says, “There is no compulsion in religion.”

However, tensions grew. Ibrahim says the Quraysh, the polytheists, drove him out and mocked him, saying, “You’re not a real prophet, you’re making this up, you’re a liar.” This led to Muhammad’s migration to Medina in 622 AD, an event known as the Hijra, which marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar. In Medina, Muhammad gained political authority and a growing following, becoming what Ibrahim describes as a warlord. This shift marked a turning point in the nature of Islam’s expansion. According to Ibrahim, Islamic teachings from this period became more confrontational and included armed struggle, or jihad, which he describes as central to Islam’s early expansion.

The discussion also explains the meanings of the words Islam and Muslim, which Ibrahim says come from a root meaning “submission” or “surrender.” A Muslim is one who submits to Muhammad’s call. Ibrahim argues that historically, Islamic rule expanded mainly through conquest. In this view, non-Muslims living under Islamic rule were expected to accept Islamic authority, pay a tax, convert, or face conflict—an interpretation based on certain readings of early Islamic law. He argues that Jews and Christians were treated as second-class citizens under Islamic rule. Ibrahim said, “If you’re a Buddhist or a Hindu, theoretically, you’re supposed to convert or die.”

The word Islam, Ibrahim explains, comes from the Arabic root meaning submission, and a Muslim is “one who submits.” In this framework, religious belief, political authority, and law were deeply interconnected. Expansion was not only spiritual but also territorial.

See Also: Who is Al Qaeda's Ayman al-Zawahiri?

According to Ibrahim, this rapid expansion was driven by the concept of jihad, which he describes as having both spiritual and military dimensions: “Jihad is a word which means to strive and to struggle.” By the time of Muhammad’s death in 632 AD, much of Arabia had come under Islamic control. However, the most dramatic expansion occurred after his death, under his successors.

After Muhammad’s death, many tribes broke away, leading to the Ridda Wars, or Apostasy Wars. Muhammad’s successor, Abu Bakr, used military force to bring these tribes back under Islamic rule. Ibrahim said, “Abu Bakr waged a new jihad against the apostates.” Abu Bakr was the first caliph; the caliphate was the system of leadership that followed Muhammad. Ibrahim said that one century after Muhammad, Islam governed all of North Africa, all of the Middle East, and had reached the middle of France.

After Abu Bakr came the second caliph, Umar, in 636 AD, overseeing rapid expansion beyond Arabia. It was during his time that the great Arab conquests began. Under his rule, Islamic forces conquered large areas such as Syria, Egypt, Persia, and North Africa. Within about 100 years, Islamic rule had spread across regions that were once central to early Christianity, including Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, and parts of Spain—“66%, let’s say, of the original Christian world.”

Ibrahim says this rapid expansion happened because Islamic religious ideas were combined with existing Arab tribal culture. He called this the genius of Muhammad. Before Islam, tribes were loyal to their own people and hostile to outsiders. Ibrahim argues that Islam kept this structure but changed it so that religion, rather than family or tribe, defined loyalty. “The Qur’an commands Muslims to hate not outside tribal people, but anyone who is not a Muslim,” Ibrahim said. The world was divided into believers and non-believers, and fighting outsiders became both a religious duty and a social obligation.

He also claims that Islamic teachings offered strong rewards for fighters. Winning battles brought wealth and captives, while dying in jihad was believed to guarantee entry into paradise. According to this view, these promises encouraged fearlessness and helped sustain military expansion.

This is how Islam, from Muhammad, a solitary figure in the deserts of Arabia—evolved into a civilisation spanning continents. Whether viewed through faith, history, or politics, Islam’s rise reshaped vast regions of the world in a remarkably short time.

Suggested Reading: